At Hope, they’ve always done things their own way, and with a very low key approach to marketing, they prefer to let their products do the talking. “Build it and they will come” could just as well be the company slogan, and the approach seems to be working – they can barely keep up with the demand for the brakes, hubs, and ever growing range of assorted goodies that are now proudly Designed, Tested, and Manufactured in Barnoldswick, England. Hope founders Ian Weatherill and the late Simon Sharp had been toying with complete bike designs for years already, and with so many components now in the line-up, it’s almost like making the actual frame was the remaining missing piece in a puzzle that began with a mountain bike disc brake in 1989. Needless to say, when we got invited to go and ride the new bike in the French Alps we were stoked to pack our bags and hop on a plane. Some trips are special.

Hope HB.160 Highlights

- FRAME: HB.160 Carbon

- SHOCK: Fox Factory Float X2 2 positon lever

- FORK: Fox Factory 36 Float RC2 160mm boost

- HEADSET: Hope 1.5" - 1 - 1/8"

- STEM: Hope AM 35mm

- BAR: Hope Carbon 780mm

- GRIPS: Hope Lock On

- BRAKES: Tech 3 E4 180mm 160mm Rear on Small

- SHIFTER LEVER: SRAM XX1 - 11 spd

- R. DERAILLEUR: SRAM XX1 - 11 spd

- CRANKS: Hope fitted with 30t spiderless ring

- CASSETTE: Hope 10-44t - 11 spd

- PEDALS: Hope F20

- WHEELSET: 27.5 35w rims Pro4 HB/110 boost

- TYRE: Maxxis High Roller II 3C EXO 2.4 (Tubeless)

- SADDLE: SDG Duster MTN Ti Alloy rails

- SEATPOST: RockShox Reverb 125 Small, 150 Medium, 150 Large, 150 XL

- BOTTOM BRACKET: Hope HB 30mm

- MSRP: GBP 7500 / EUR 9000

- Availability: September 2017 (early 2018 in the US)

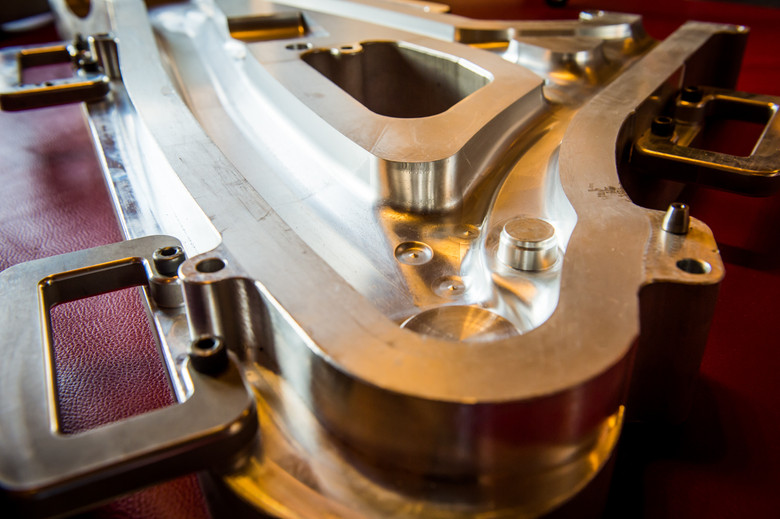

The HB.160 was not meant to go on sale. It started as a design exercise and first saw light at various trade shows under the name HB211, really just for the satisfaction of seeing it completed. After years of playing around with various metal designs, the company eventually settled on carbon for the HB project (with an aluminum rear end). This seems like a curious choice at first, since getting carbon molds done is usually a very expensive part of the manufacturing process and certainly not the first choice for any kind of prototype or small batch production work – but Hope has an ace up its sleeve here. It turns out that the molds needed to lay up the carbon can be CNCed from aluminum, and if there is one thing the boys and girls at Hope know about, that would be it. They claim they can now go from a drawing to a completed frame in just 6 weeks time, and that it's now actually easier for them to machine a mold and lay up a carbon prototype than it would be to get full aluminum frames welded.

How hard can it be?

Additionally, the UK is brimming with Formula 1 and aerospace manufacturing talent, and Hope was able to consult locally for the carbon expertise needed to pull off the project. They started with simple parts like a seat post or a handlebar, and worked their way up from there. “How hard can it be?” is a saying that can often be heard around the Hope team, and although the HB.160 project proved that it can in fact be quite hard indeed, the result speaks for itself. It wasn't too hard for this crew at least. In keeping with company tradition and in order to ensure complete control over both quality and health and safety regulations, carbon production has been kept fully in-house, right there in the Barnoldswick plant.

After having settled on a 160mm enduro bike for the HB project, the design team put everything else up for debate. Nothing was taken for granted, and no standard was sacred. In fact, the team deliberately set out to find the best solution to every area of the bike, and rather than rely on existing standards, the HB.160 has ended up almost standard-less.

Boost That Isn't Boost

Hope produced a specific rear end and hub to achieve a dishless wheel build. They moved the drive-side chainstay out and increased the chainline to give more clearance around the bottom bracket (this was pre boost, but realistically it has achieved the same thing). Additionally they brought the non-driveside chainstay in to create a narrower, 130mm dropout and they positioned the rotor/caliper as close as possible to the spokes. The special hub is fitted with a 17mm thru axle and 25mm location spacers for maximum stiffness. The result is a rear triangle that is actually narrower at the chainstays whilst the wheel still benefits from Boost-like spoke bracing angles and a dishless build.

Bottom Bracket

The BB is a Hope-specific variation built around the company’s own 30-mm spindle crank. It’s a hybrid of a traditional screw-in and a press-fit BB, in an attempt to combine the best of both worlds. The design features a center tube that sits between the bearings and takes up any side loads. The offset layout of the rear end creates plenty of room for mud clearance even with the reasonably short, 435mm chainstays.

A New Brake Mount

The rear brake is radially mounted, which basically means it is symmetrically positioned along a straight line out from the center of the wheel. The advantage to this system is that there are no other variables to account for when changing rotor sizes, unlike the current standards where the brake caliper’s position relative to the wheel changes as well as its distance from the center. In the words of the brake designer himself:

It is really frustrating to model things perfectly on the screen and accurately machine them, only to have the fitment compromised by there being no standards when you move away from the usual 160mm mount. Of course, it is not stopping the brake working but it somehow looks like a bodge!

Suspension

For the suspension design, the team eventually settled on a Horst-link layout, which was made quite progressive to ensure compatibility with both air and coil shocks. They also aimed to provide good pedaling support and snappy handling. These suspension design choices meant they had to forego space for the water bottle, a decision that was not taken lightly but that was ultimately considered to be the appropriate compromise.

Geometry

Rather than jump blindly onto the “lower, longer, slacker” bandwagon, Hope took a long hard look at what they ride and how they like to ride it, and ended up with quite conservative numbers when it comes to reach and overall length of the bike. Favoring a lively, maneuverable, and comfortable bike that is as much fun to ride on tight switchbacks as it is on the open trail, the HB.160 wasn’t intended to be a pure race machine (although it has already proven itself on the race track with a couple of UK National Championships and some impressive EWS stage results to its name).

On The Trail

There’s no denying that the HB.160 is a beautiful bike. From the carbon weave to the stunning CNC work of the rear triangle (which is made of aluminum both to keep costs in control as well as provide better durability in this exposed area), everything about the frame screams custom. Add to that a smattering of Hope parts, and we were like kids in a candy store when setting up our ride. On the topic of candy, customers will be able to choose the color of the finishing kit of their HB.160 from the standard 6 Hope colors – provided you can get on the very short list of people who will be able to buy one that is. Much like a Model-T Ford, the frame can be any color you want as long as it’s black.

We spent two days in the lovely area of Serre-Chevalier riding the HB.160. Better known as a winter destination, the resort has recently embraced mountain biking as well, and a small bike park with a big fun factor greeted us for the first day out on the new bike. Perhaps because it closely mirrors the geometry of bikes we have been used to riding for a few years now, the HB.160 was very easy to get along with. This 1m84 tester rode a size large, which provided a good compromise between fun and stability. If you like a longer bike, you can always size up, provided you can deal with the extra seat tube height.

We were especially impressed by the composure of the rear end, the suspension striking a fine balance between bump absorption and progressiveness.

In the bike park, we rode everything from bermed flow trails to natural, rugged chutes, and the HB.160 proved to be a reliable and fun-loving companion for all of it. We were especially impressed by the composure of the rear end, the suspension striking a fine balance between bump absorption and progressiveness. In fact, we’d go so far as to say that this is one of the better Horst-link executions we have come across to date. The HB.160 will be sold with the air shock featured on our test bike, but the bike will handle a coil shock as well thanks to the progressiveness of the linkage.

For day two, we headed out on an Alpine adventure to enjoy more natural tracks and a bit of climbing. Once again, the HB.160 was a worthy companion. We wouldn’t go so far as to call it sprightly, but it certainly puts in a good showing on the uphills as well as the downs. Pedal bob is well controlled even before you reach for the lockout lever on the shock, and the seat tube is steep enough to keep your weight over the pedals even on tougher climbs.

Much like in the bike park, the HB.160 mustered up to any task we could present it with on the natural, technical tracks surrounding the amazing Serre-Chevalier valley. The somewhat conservative sizing really came into its own as soon as the trails got twisty and technical, but the bike also never felt excessively twitchy or out of control in the faster, rougher sections. Riding the trails blind, we certainly got in over our heads well before the bike ever did.

So what with all those in-house standards then? It would be far-fetched to say that we noted a specific improvement as a result of any of the bespoke solutions the Hope team came up with, but what is also clear is that there are no negative consequences, at least not when it comes to the bike’s handling. The HB.160 is a very capable and fun-loving enduro bike, that we would have no qualms about making our one bike for a couple of seasons. Of course, proprietary standards mean that you are essentially locked in when it comes to replacing parts, but that is really the whole point of this bike anyway. Hope wanted to make a complete bike because they can, and anybody who buys into the concept won’t be in a rush to replace any components – this thing is straight up custom off the shelf to start with. The production runs will be small, and if you are lucky enough to get your name on the list (and have the means for it!), you’re certainly getting a very special bike for your money.

Build Kit

The HB.160 will only be sold as a complete bike, and there will only be one model available. Suspension duties are taken care of by the excellent FOX 36/Float X2 duo, with SRAM’s 11-speed XX1 derailleur in charge of shifting. After that, except for the RockShox Reverb dropper post, the Maxxis tires, and the SDG saddle, everything else on the HB.160 is made by Hope. Hubs, rims, brakes, crank, cassette, BB, headset, stem, handlebar, grips, seat post clamp and pedals were all Designed, Tested, and Manufactured in-house. Having previous experience with most of these parts, we knew what to expect coming in: smooth, trouble-free performance all around. This stuff is good, make no mistake about it. If you want to know more, here is a list of Hope goodies we have previously tested:

What's The Bottom Line?

Sometimes quirky but always inspired, UK manufacturing has a fine tradition of doing things its own way, and the HB.160 is no different. A bit off the beaten path but utterly compelling, it breaks with tradition to deliver an exclusive ownership experience that cannot be matched by a mass-produced bike coming off an assembly line, no matter how sophisticated it may be. Sure, GBP 7500 is a lot of money for any bike, but for those lucky enough to be able to lay their hands on one, they’re getting something that money can’t buy: a unique bike made only for the love of the game, by people who just wanted to see if they could pull it off. How hard could it be?

More information at: www.hopetech.com.

About The Reviewer

Johan Hjord loves bikes, which strangely doesn’t make him any better at riding them. After many years spent practicing falling off cliffs with his snowboard, he took up mountain biking in 2005. Ever since, he’s mostly been riding bikes with too much suspension travel to cover up his many flaws as a rider. His 200-pound body weight coupled with unique skill for poor line choice and clumsy landings make him an expert on durability - if parts survive Johan, they’re pretty much okay for anybody. Johan rides flat pedals with a riding style that he describes as "none" (when in actuality he rips!). Having found most trail features to be not to his liking, Johan uses much of his spare time building his own. Johan’s other accomplishments include surviving this far and helping keep the Vital Media Machine’s stoke dial firmly on 11.

Photos by Johan Hjord and Roo Fowler

View replies to: So British | Riding the Hope HB.160

Comments